How do we learn to spell?

There are many misconceptions about learning to spell and write. They are misunderstood by children, parents and even some teachers. The standard way to teach spelling in schools has generally been through the memorisation of lists of words and learning rules.

But as I pointed out in a previous post on spelling (here), it is impossible to learn the number of words that we use as adults by memorising lists. So, while spelling lists might help children to memorise some words, proficient spelling requires the development of a range of generic skills that are necessary for effective spelling.

The stages of spelling growth

Children begin to learn about spelling in the preschool years in rich language environments that support them as readers, offer them many varied opportunities to write, and encourage them to explore and play with words. There are many skills that children need to learn as part of writing for varied purposes. Most children move through a series of stages in spelling development. While these are never 'neat' and discrete, they are recognisable with most children. Understanding the stages will help us to choose the right strategies to help them become better at spelling. Gentry and Gillet (1993) suggest that most children move through the following stages:

Pre-phonetic - this occurs very early on (from age 2-3 years) and involves the child trying to form letters or simply drawing symbols that are an attempt to represent letters.

Semi-phonetic - at this stage (age 4 and up) the child is able to write most letters and even some approximations to words, and they know some of the sounds they make (as well as letter names).

Phonetic - eventually the child is able to represent sounds with the appropriate letters (single letters at first). They also begin to represent words in more conventional ways, but often they will use invented spelling patterns where the word has some (but not all) of the letters correct. This begins for most children from 5 years of age.

Transitional - at this stage children (aged 6-7 years) are able to think about the word, develop visual memory and begin to internalise the spelling pattern and know when words 'look right'.

Conventional - at this more mature stage the child can use both visual and auditory skills and memory as well as meaning based strategies (like seeing how the word fits in context). Now they can write multisyllabic words from memory and find the learning of new words much easier as they apply their skills and strategies from one situation to another. This occurs for most children from about 8 years of age but continues to develop throughout the primary years of schooling.

How can I help children to be better spellers?

Most children learn quite naturally to experiment with writing and spelling. This occurs in varied ways. For example, as we read to toddlers we point to words and language devices; this in a sense is the beginning of spelling awareness (not just reading). Early memorising of rhymes and songs, playing with sounds and word play of all kinds is also the beginning of spelling. The 10 necessary skills outlined in a previous post (here) are acquired both incidentally ('caught') and by explicit help ('taught') and instruction. There are a variety of more explicit strategies that teachers and parents can use to support spelling development in the primary school years. I will share 8 key strategies that are helpful.

1. 'Have a go' strategy

This is a strategy for trying to spell unknown words as part of the writing process (ideal for children aged 6 years and older). Teach your child (or children) to apply the following strategy when they need to spell an unknown word.

- Ask yourself, have I seen it before?

- Say the word out loud and try to predict how many syllables you can hear.

- Ask do I know any other words that sound almost the same?

- How are those words spelt?

- 'Have a go' at spelling it (Aussie vernacular for trying to do something).

- Ask yourself, does the word look right?

- Have additional attempts at getting the word right.

This is a strategy that you can teach children new words at any age, once they have started to write. It has three simple steps.

Step 1 - When you need to remember how to spell a new word look at it carefully, say it out loud, examine the number of syllables, any unusual grapheme/phoneme relationships etc.

Step 2 - Cover the word

Step 3 - Try to write it from memory

3. Here is a collection of self-help strategies - children as young as 6 can be taught to try to learn new words.

- After covering the word try to picture it in your mind.

- Uncover the word and trace the letters, cover and try again

- Look at the new word, break it into syllables. After studying the syllables cover the word and try to write it.

- Look at the new word and try to memorise the most difficult part of the word (e.g. the 'ght' in sight).

- Check your writing environment for the word, or one like it (wordlists, other writing, dictionaries etc).

An alternative to some of the more visual strategies above is a simple auditory strategy that can be used as follows. The key to the strategy is to keep encouraging the child; avoid making the child feel like spelling is one big test session.

- Ask the child to write the word after saying it slowly at least twice.

- Encourage them to listen to the word as they say it and to try to write the sounds in order.

- Now repeat the word breaking it into its parts or syllables; for multisyllabic words some teachers have the children clap as they say the syllables out loud.

- Encourage the child to try to think of other words that sound the same, and to think about how the other words are written.

- Finally, have the child write the word (bit by bit) as they say the syllables.

5. Word family approaches

Many young children will benefit from an approach that presents words in sets that have similar phonological elements. For example, you might present your children with a group of words ending in 'ight', others that begin with 'thr' etc. You can have fun forming the lists with your child (or children), writing them down, then trying to remember them. There are many good spelling games that support this type of approach.

6. Using a word connection strategy

This is a strategy that supports the development of the 'connection' skill mentioned in my previous post on spelling. It is a meaning-based strategy.

- Ask the child whether the word to be spelled reminds them of another word they know.

- Encourage them to explain how it is similar and then use the information to help spell the word.

- Then encourage them to think of other words like these words and to use parts of the new associated words to write the new word.

- Encourage them to think of places or contexts where they might have seen this word used.

- Then try to write the new word.

7. Morphemic (meaning-based) strategies

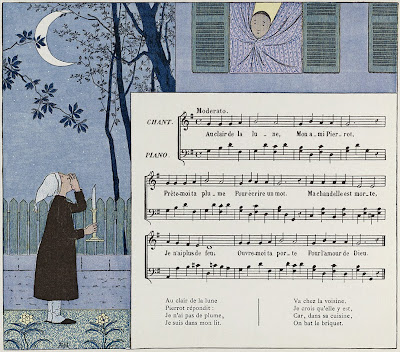

|

| Photo courtesy Wiki Commons |

For older children (aged 11 and up) you might also consider exploring Latin roots to aid spelling. For example:

- 'mare' meaning 'sea' as used in marine

- 'pedis' meaning 'foot' as used in pedestrian

- 'gress' meaning to walk as used in 'progress' and 'transgress'

- 'tract' meaning to 'draw', 'drag' or 'pull' as used in 'attract' and 'contract'

- 'hyper' meaning 'excessive' or 'excessively' as in 'hyperactivity'

8. Mnemonics

Mnemonics are devices that help us to remember things. I'm not a big fan of this approach but sometimes it helps when a child (or adult) just can't manage to avoid confusing two spellings. So it's usually a strategy that people use to remember how to spell words that they get wrong habitually. A mnemonic simply helps to remove confusion or narrow the options for spelling. There is a down side to mnemonics though. If you use them too much you tend to reduce the use of other key spelling strategies, reducing your confidence and risk-taking as a writer. A simple example of a mnemonic applied to spelling is one used to help us know the difference between 'affect' and 'effect'. It is based on the word 'raven' used as an acronym:

R - remember

A - 'affect'

V - verb

E - 'effect'

N - noun

Online resources

There a variety of online resources that aim to help children learn more about spelling. Most are simply ways to memorise lists of words but even this basic strategy has a place, particularly for irregular words that are exceptions to our languages rules. An advantage of online resources is their appeal for young children and the instant feedback that children receive. One useful site is Kidsspell.com (here) that offers varied wordlists, a free spellchecker and thesaurus, games to play etc. You can also find sites that allow children to apply strategies like the ones I have described online (see for example application of 'look, cover, write' on this site). You can find other games and activities at 'Games aquarium' (here) and others on the Kent Junior High School site (here). But remember, spelling is much more than learning lists and playing online games.

Summing up

Language is always undergoing change (see my post on 'English, the Inventive Language') and with increased use of mobile phones, Facebook, Twitter and so on, it is bound to change more than at any other time in history. But accurate spelling is still important. With spellcheckers everywhere and the preparedness of the young to invent their own language online, some suggest that the teaching of spelling isn't as important, but this of course is nonsense. Conventional spelling is still important - let anyone come up with an invented version of your name and see how you react. Accurate and consistent spelling is not just about conventions and good taste; it is important for the communication of meaning.

Spelling is an integral part of reading, writing, speaking and listening. It is learned as we use language for real purposes. But it isn't simply 'caught'; there is an important need for teaching. Most of this 'teaching' does not occur through memorising lists of words, but rather as we draw children's attention to variations in the English language. We need to show them simple rules for spelling, offer strategies for getting words right, provide tools for seeking correct spellings (including dictionaries and spell checkers), give them new knowledge about how our complex language works and as we simply encourage them to use and 'play' with words.

Other links and resources

'Guide to English Spelling', David Appleyard (here)

'Guide to English Spelling', David Appleyard (here)My previous post on 'Twenty Fun Language & Thinking Games for Travellers' has some relevant activities that could be adapted (here).

Christine Topfer & Deidre Arendt (2010). Guiding Thinking for Effective Spelling, Melbourne: Curriculum Corporation (here).

Diane Snowball & Faye Bolton (1999). Spelling K-8: Planning and Teaching, York (ME): Stenhouse Publishers (here).